Modern monetary theory and monetary sovereignty

Private savings are key for government borrowing

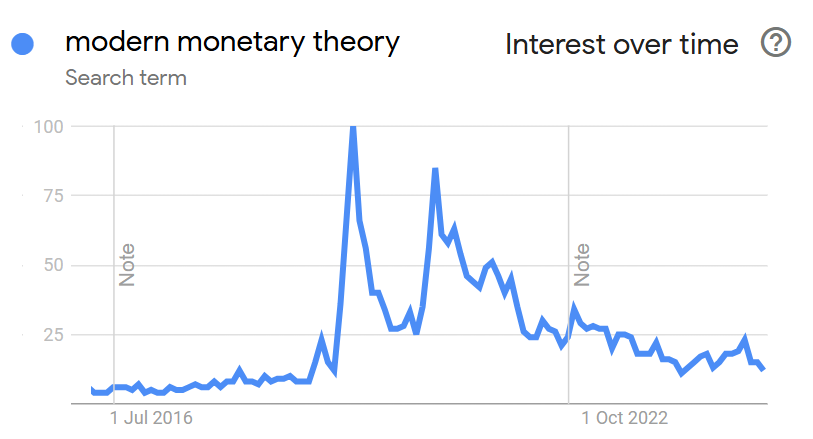

Modern Monetary Theory (MMT) gained significant attention in 2019 when U.S. lawmaker Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez used it to support her policy proposals, including the Green New Deal. Its prominence grew further with the release of Stephanie Kelton’s book, “The Deficit Myth: Modern Monetary Theory and the Birth of the People’s Economy”, in June 2020. MMT’s rise can partly be attributed to the inadequate economic response to the 2009 recession in wealthy countries, particularly in Europe, where premature austerity and a reluctance to expand fiscal deficits likely contributed to prolonged economic weakness.

In contrast, the U.S. response to the COVID-19 pandemic in 2020 was massive and unprecedented, with expanded spending totaling $3.9 trillion, including the $2.3 trillion CARES Act. This spending included enhanced unemployment benefits and direct payments to individuals. The American Rescue Plan, or "COVID-19 stimulus package," introduced in 2021, further fueled the debate on the importance of fiscal sustainability. The U.S. economic response to the pandemic was among the most robust of any advanced economy, with fiscal measures playing a key role.

However, the situation has since changed. As previously discussed, fiscal policy can significantly impact inflation. Therefore, this expansionary fiscal response to the pandemic, combined with supply-side issues relating to China’s lockdowns and finally Russia’s invasion of Ukraine triggered a surge in global inflation in 2021-2022.

The rise in inflation since 2021 has led to a decline in interest in MMT. Nevertheless, the theory still raises intriguing questions. For example, why can some countries, like the U.S., spend large amounts without worrying much about fiscal sustainability, while other countries, such as many in Africa, with lower levels of debt, have to rely on the IMF and other international institutions for debt relief?

What is MMT?

The name MMT is somewhat of a misnomer. It is not really new, strictly about monetary policy or a technical theory. Noah Smith calls it a meme or an idea — “a set of arguments for a specific policy, rather than a fully laid-out description of how the economy works”.

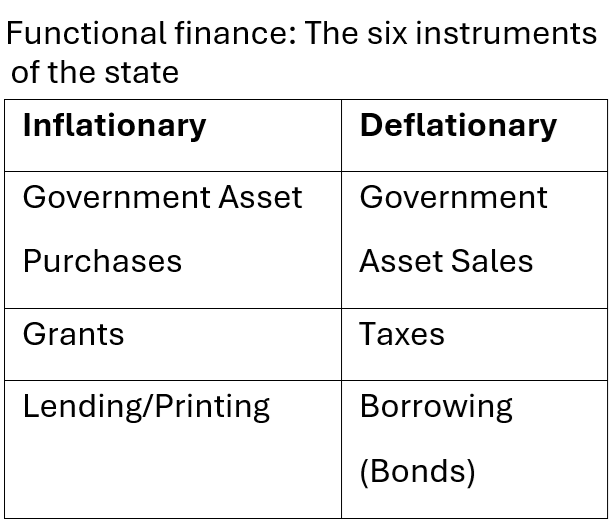

MMT is largely based on Abba Lerner’s functional finance theory from the 1940s. This approach distinguishes between two types of unemployment: deflationary and frictional. Frictional unemployment occurs when workers have the wrong skills or are in the wrong location. In contrast, deflationary unemployment arises from insufficient demand. To achieve full employment, deflationary unemployment must be addressed. Functional finance aims to do this through the use of six state instruments, which can influence inflation or deflation. Since money is considered a creation of the state, the amount needed to fund these instruments is not a limiting factor.

This shift has several policy implications, including moving away from traditional “sound” finance towards a more functional approach aimed at controlling inflation. For instance, in this “functional” framework, taxes and government borrowing are viewed not as state revenue but as methods to withdraw money from public circulation, thereby helping to reduce inflation. Traditional concerns of “sound” finance, such as increasing debt or money printing, might be set aside if inflation remains under control. Essentially, functional finance emphasizes coordinating monetary and fiscal policies to prevent both inflation and deflation while striving for full employment.

MMT borrows a lot from functional finance, such as seeing the money resources of the state as unlimited, using fiscal policy to control inflation, and aiming for full employment. Where MMT is novel is the use of a job guarantee paid for by the state or using the state as an employee of last resort. MMT economists state that this could achieve full employment without the expected inflationary pressures. The job guarantee would be at a wage equal to or below the minimum wage as to not complete with the private market and limit rising wage pressures and would act as a “counter cyclical fiscal stabilizer”. The idea is that a job guarantee would increase the capacity of the real economy by increasing aggregate supply, hence the cost of paying for it would not be inflationary. However, the idea that a state’s money resources are unlimited only applies to countries with monetary sovereignty.

Monetary sovereignty

To obtain monetary sovereignty, Bruno Bonizzi and others cite three main elements:

“Government issues the national currency and imposes tax liabilities in that currency.

The currency is fully floating and non-convertible to any other currency or commodity.

There is no foreign denominated debt.” (p.49)

These factors are not binary and there is an argument to be made that monetary sovereignty lies on a spectrum. However, more is needed to figure out where countries lie on this spectrum. This is particularly relevant for developing nations, which face additional constraints that limit their policy autonomy, such as the willingness of the private sector and foreign investors to hold bonds in the domestic currency.

In "A Skeptic’s Guide to Modern Monetary Theory", Greg Mankiw acknowledged that "a currency-issuing government can always print more money when a bill comes due". However, he disagreed with the idea that a country issuing its own currency can never become insolvent in that currency. He pointed out that, under our current monetary system where interest is paid on reserves, printing money will end up as reserves in the banking system, and the government will need to pay interest on those reserves. This means that printing money is effectively borrowing from the banking system. To cover the cost of interest, the government could either print more money or ignore the issue, both of which could lead to higher inflation and eventually hyperinflation. Additionally, to avoid hyperinflation, a government might default on public debt denominated in its own currency. Therefore, the elements discussed by Bonizzi for achieving monetary sovereignty are incomplete.

The role of private wealth in achieving monetary sovereignty

To avoid significantly raising borrowing costs or increasing inflation if the government prints money, interest rates need to be kept relatively low. This means a low interest rate on bank reserves is essential for a country to monetize its debts and achieve monetary sovereignty.

Several factors influence interest rates. Fiscal deficits and high inflation can drive up interest rates, so having institutions like an independent central bank that manages inflation expectations is crucial for keeping rates down. Additionally, having a certain level of domestic savings is important for lowering interest rates. Generally, higher private wealth leads to lower interest rates due to the straightforward economic relationship between savings and interest rates. Deep and liquid financial markets can utilize these savings to fund the state and further lower rates. Thus, the level of private wealth and its impact on interest rates is important for defining a country's monetary sovereignty and its ability to borrow and manage its debts.

Sectoral Balances

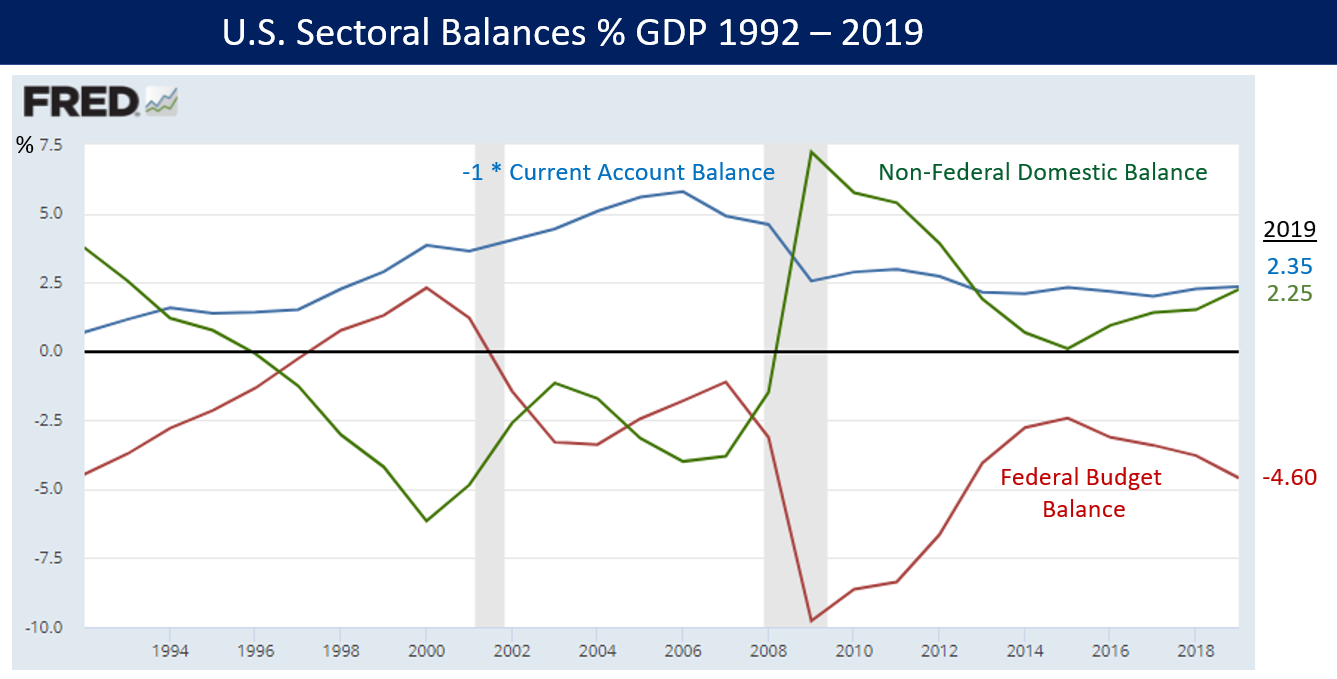

The way domestic or foreign savings can support state borrowing is reflected in the sectoral balances of the economy. Private wealth often flows into government debt because government bonds provide a secure place for the private sector to park surplus savings. Sectoral balances are helpful because they show that increases in government debt must correspond with surpluses in the non-government sectors, including household savings, firm savings, and the foreign sector. The total balance across these four sectors must always sum to zero.

In simpler terms, an excess of private savings over investment must be balanced by either a fiscal deficit or a current account surplus. Countries with consistently high private savings tend to have either substantial fiscal deficits without causing inflation or large current account surpluses (or both). This is evident in Japan, which has the highest government debt in the world at around 270% of GDP, yet faces little concern about default. This stability is partly due to Japan’s low interest rates, which are a result of its high savings rate. Japan is also the world’s largest creditor nation, thanks to decades of current account surpluses. Therefore, Japanese businesses and households save so much that they can lend record amounts to both their government and to the rest of the world.

Conclusion

Other institutional factors play a role in ensuring monetary sovereignty. Trust in well-managed banks and financial institutions is essential for people to feel secure placing their life savings with them. Clear and secure property rights are also necessary. Additionally, a credible government is important: if a government is at risk of defaulting, borrowing costs will rise. Therefore, for public deficits to be balanced by private sector surpluses, a country needs a certain level of private wealth, some level of financial development, strong institutions to control inflation and prevent financial repression, and a credible government. This is along with the factors mentioned by Bonizzi, such as having limited foreign denominated debt, a flexible exchange rate and issuing in the domestic currency.

Overall, while MMT (and its predecessor, functional finance) offers valuable insights on when, how, and why governments should borrow. It overlooks the crucial role of savings and the institutions that support them.