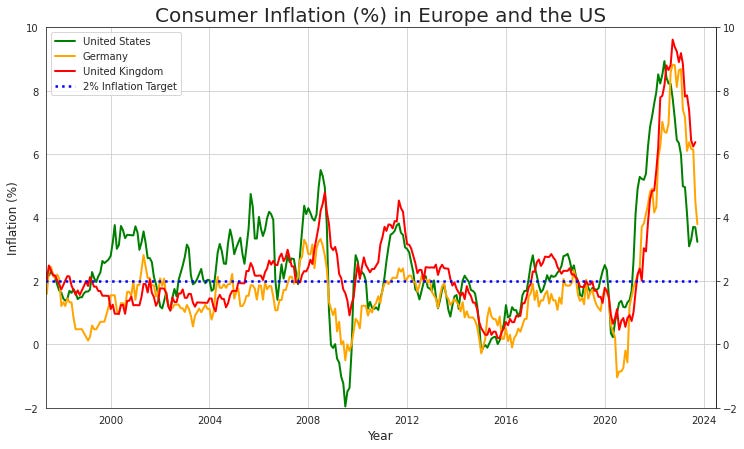

Most of the world has been dealing with a cost-of-living crisis in which the prices of almost everything have rapidly risen. The current surge in inflation has multiple potential causes, such as expansionary monetary and fiscal policies, supply shocks, corporate profits, wage hikes, and shifting expectations. A debate surrounds whether this inflation uptick is temporary, deemed "transitory," or if it reflects more structural changes. Understanding the theories of inflation helps to answer this question.

Quantity theory of money

The earliest theory of inflation, known as the quantity theory of money, took shape in a relatively complete form in the debate on the causes of the "Price Revolution" in 16th-century Europe. Jean Bodin played a key role in formulating this theory, stating that the price level is directly proportional to the quantity of money. The "Price Revolution" itself was attributed to the influx of gold and silver from the Americas during that period. Another historical example supporting this theory is Mansa Musa's gold spending in Egypt during the 14th century, which, on his way to Mecca, significantly increased inflation in Egypt and devalued the price of gold.

Despite its historical significance, the quantity theory of money has its flaws, notably its assumption of a constant velocity of money. This assumption doesn't always hold true. Over the past few decades, possibly due to the increasing use of financial credit, the velocity of money has declined.

Demand and supply

Inflation is also influenced by the interplay of aggregate demand and supply. When the demand for goods and services surpasses the available supply in an economy, it can trigger a rise in prices. Strong demand also allows producers to command higher prices for their goods. Alternatively, if the costs of producing goods and services increase — whether due to rising wages, elevated energy expenses, or an increase in raw material costs — producers may pass these costs to consumers through higher prices.

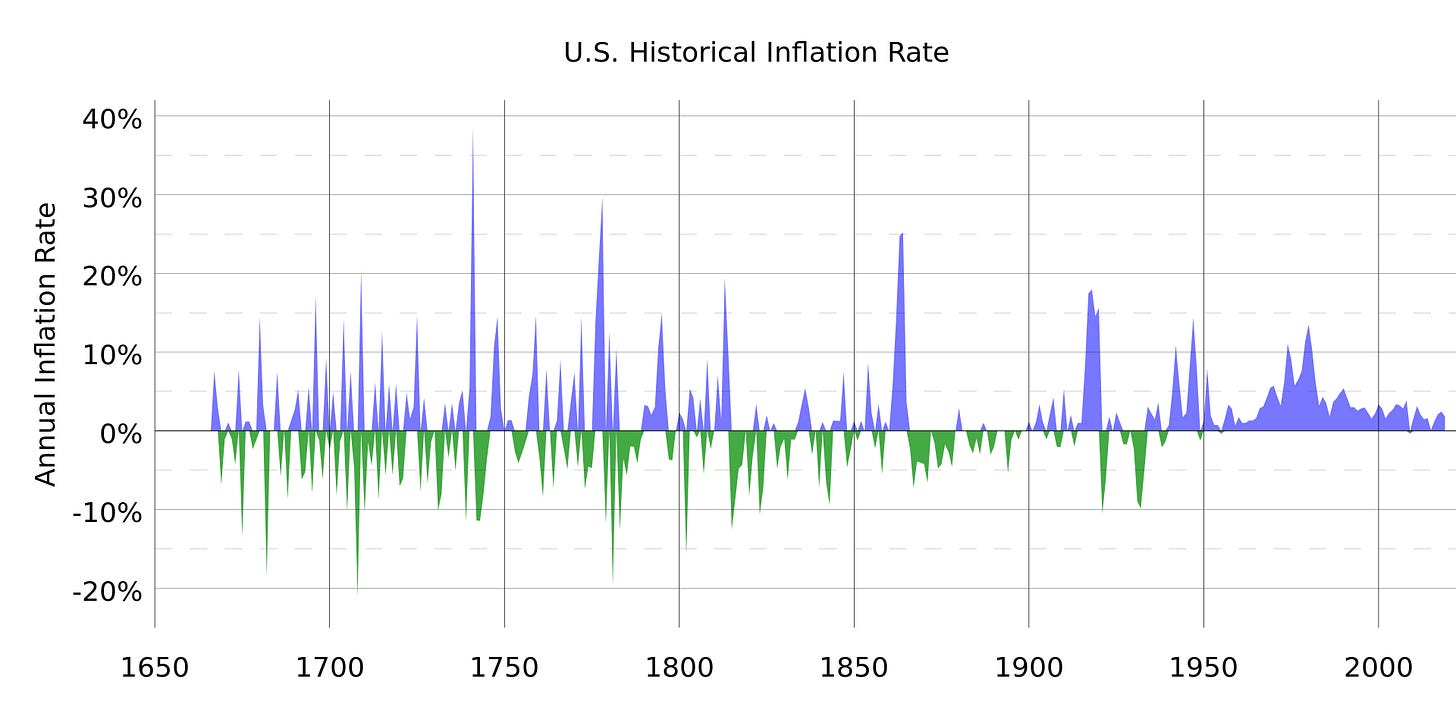

An interesting historical example of the role of supply is the Second Industrial Revolution, spanning from 1870 to 1912. The surge in productivity, driven by new machines, led to an increase in supply, resulting in a period known as "the Great Deflation". During this time, living standards improved as goods became more affordable, while real wages — accounting for inflation — rose.

The opposite took place during the Great Depression when a lack of demand led to a decline in inflation. This period coincided with a more financially oriented economy, where debt played a more prominent role. Deflation, particularly in this context, is far more damaging as it increases the real value of debt, further depressing demand.

In his notable work "A Treatise on Money", John Maynard Keynes argued that the Great Depression was primarily a consequence of insufficient aggregate demand and that the velocity of money was highly variable. He further argued that government spending could significantly bolster aggregate demand, even if such spending was perceived as wasteful. Keynes was largely accurate in emphasizing the government's role in limiting the costs of economic cycles. This viewpoint led Milton Friedman to state "We are all Keynesians now", acknowledging the widespread acceptance of Keynesian economics.

Monetarism

Monetarism, emerging as a response to Keynesian economics, revived interest in the quantity theory of money. In their influential work, "A Monetary History of the United States, 1867-1960," Milton Friedman and Anna Schwartz delved into the role of money in shaping output and inflation. Contrary to the prevailing Keynesian view, they famously asserted that the Great Depression was not caused by insufficient government spending but rather by a contractionary monetary policy implemented by the US Federal Reserve. Essentially, a governmental entity had exacerbated the contraction more than it would otherwise have been. Their research also led them to the conclusion that the supply of money had a significant impact on short-term output and long-term inflation. This prompted Friedman to declare that “inflation is always and everywhere a monetary phenomenon’’.

The Phillips Curve

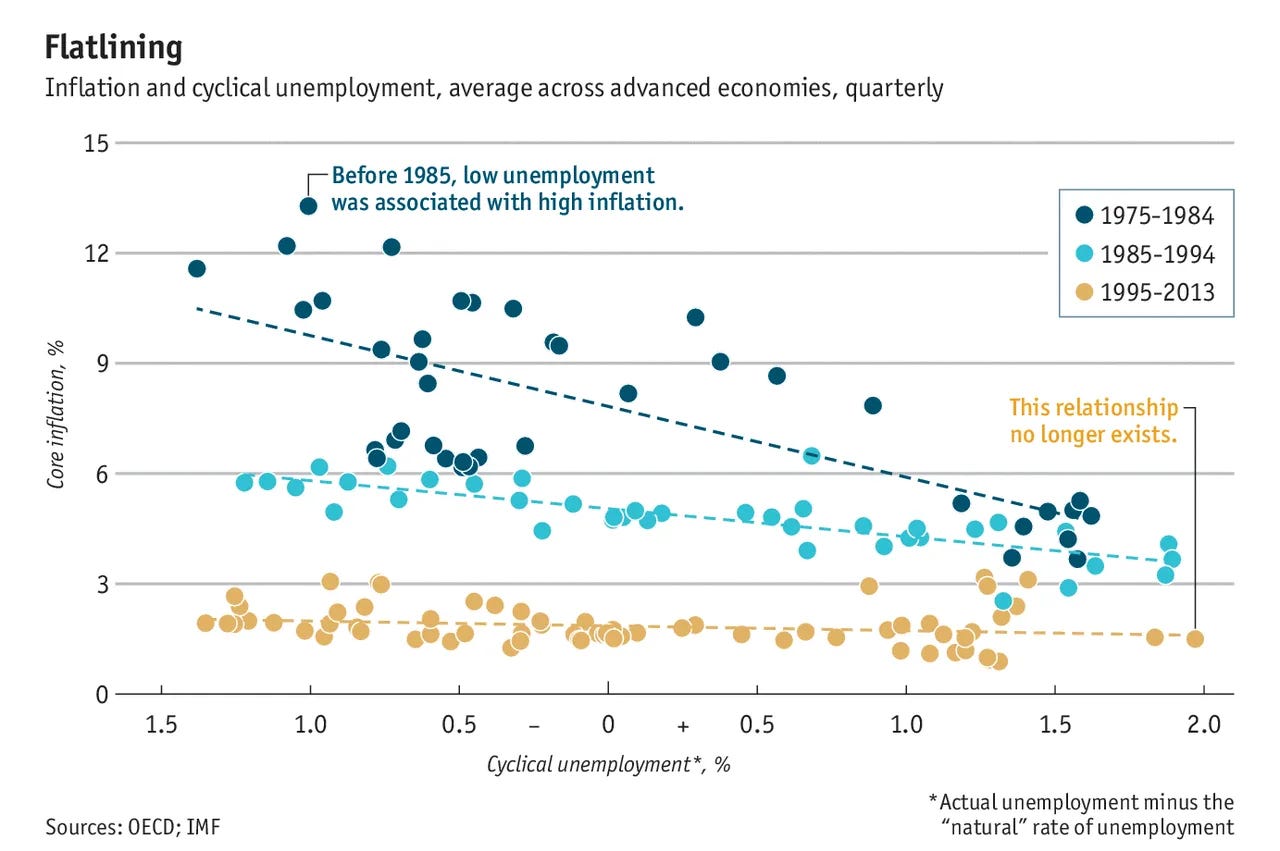

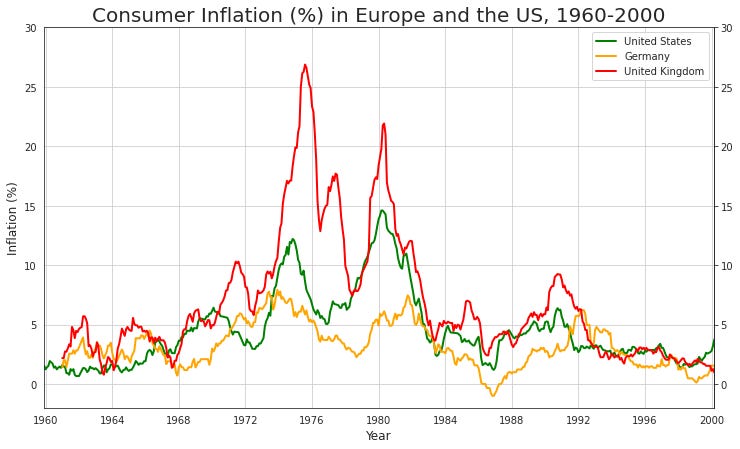

Various other theories attempt to explain inflation, one of which links it to the unemployment rate. This idea has its origins in Bill Phillips’ study of unemployment and changes in wages in the United Kingdom from 1861 to 1957, where he identified an inverse relationship. Although Phillips did not explicitly connect unemployment and inflation, Friedman and Edmund Phelps later utilized this concept to formulate the Phillips curve. The idea of the Phillips curve is that there is a “natural” rate of unemployment, which is the level of output above which any increases would be inflationary. While a relationship exists, the debate surrounding the Phillips curve is complicated. The curve essentially faltered during the "stagflation" period in the 1970s, a period of both high inflation and unemployment. More recently, it has also weakened, influenced by demographic factors — slowing and aging populations have diminished the link between unemployment and inflation, this is especially true in Japan.

Expectations

Expectations play a crucial role in fuelling inflation. When individuals and businesses anticipate a rise in prices, their actions may inadvertently contribute to inflation. For instance, if workers foresee an increase in the cost of living, they might demand higher wages. Simultaneously, businesses may choose to raise prices to offset expected higher labour costs. Thus, inflation can be triggered by a self-reinforcing cycle where elevated wages prompt higher prices, and these higher prices, in turn, drive demands for increased wages. This cycle of inflation, fueled by heightened expectations, is slow to develop and slow to disappear.

Milton Friedman argued that accounting for expectations fixes the broken Phillips curve. His view was that workers engage in wage negotiations with a focus on their anticipated real wages, not current wages. The initial Phillips’ study focused on current wages, however, Friedman pointed out that Phillips wrote his paper when everyone assumed that nominal prices would be relatively stable. Friedman suggested that rephrasing the Phillips curve in terms of expected or "anticipated" real wages clarifies the picture. Following Friedman's insights, the use of inflation expectations and the Phillips curve relationship gained prominence in macroeconomic models.

Fiscal theory of the price level

The fiscal theory of the price level suggests that if a government's fiscal policy is unsustainable and it cannot repay its debt through tax revenue, it may resort to inflating the debt away, leading to increased inflation. Expectations play a crucial role; if businesses anticipate that the government will print money to settle its debt, they might pre-emptively raise prices, creating a self-fulfilling prophecy of inflation. Therefore, maintaining fiscal discipline, such as a balanced budget, is essential for keeping inflation low over the long term. The implication of this is that government fiscal policy, including present and future spending and taxes, is the primary determinant of inflation as opposed to monetary policy. This is probably the most recent theory of inflation.

Theories of hyperinflation

Clearly, there are many theories of inflation, and the recent surge in inflation has highlighted the importance of demand and supply shocks in the short run. However, this still doesn’t answer whether the recent inflation will be sustained or not. At times, the most effective method for understanding a theory and its underlying logic involves stretching it to extreme terms. In the context of inflation, this entails examining the root causes of hyperinflation.

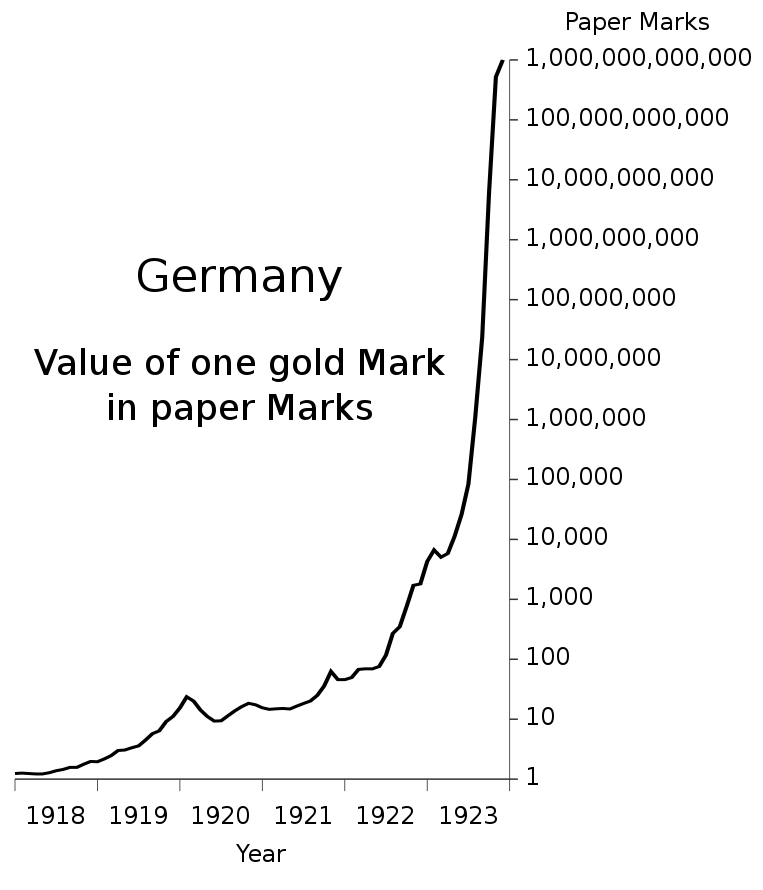

When a country surpasses its debt limit and is unable to roll over its debt, the probable outcome is a sovereign default. The alternative to default is to depend on central bank financing, leading to a swift expansion of the money supply and an acceleration of inflation. Episodes of hyperinflation — defined by Phillip Cagan as periods with inflation exceeding 50% per month — in the 20th century can be divided into two main phases: one in Europe after World War I and another in the 1980s and 90s mostly in Latin America. More recent instances include Zimbabwe and Venezuela. Interestingly, between 1946 and 1986, there were no periods of hyperinflation anywhere which can be likely explained by the Bretton Woods system of fixed exchange rates and the financial repression required to maintain it.

The seminal paper on hyperinflation is Thomas Sargent’s 1982 study of four inflation episodes in Europe in the 1920s after the first world war, these were Austria, Hungary, Germany, and Poland. Each of these countries faced large budget deficits which were funded by central bank monetised debt and all four faced episodes of hyperinflation. The hyperinflation rapidly increased the fiscal deficit, this is due to spending being current while lagged tax revenues are based on a lower price level. The inflation episodes ended after “the establishment of an independent central bank and a move toward a balanced government budget” according to Sargent. Similar conclusions were made by Dornbusch and Fischer in the role of decreasing the budget deficit and establishing an independent central bank. Episodes of hyperinflation after WW1 were rapid in both their start and end, with the demand for domestic money rapidly recovering. As soon as the old money was replaced and redenominated, it was as if these hyperinflation episodes had never occurred.

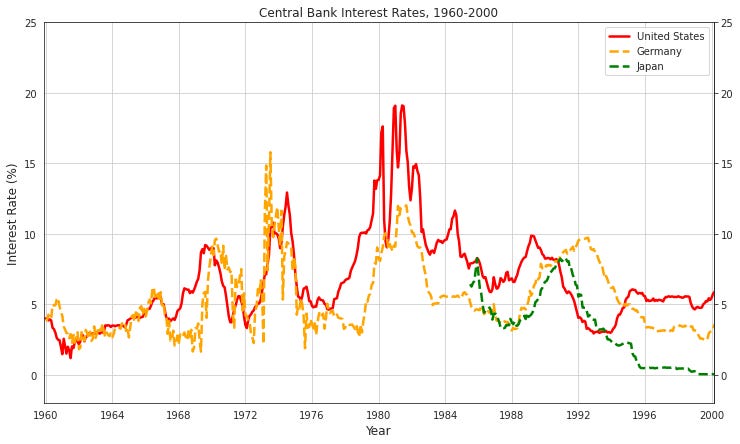

In contrast, modern episodes of hyperinflation have not been short and often preceded by long periods of very high inflation. Carmen Reinhart and Miguel Savastaro in “The Realities of Modern Hyperinflation” studied modern hyperinflation episodes in the late 80s and early 90s in Argentina, Bolivia, Brazil, Peru, and Ukraine. The episodes in South America were related to “a worsening international economic environment” related to the “Volcker shock”. This shock occurred when Paul Volcker rapidly increased U.S. interest rates to address elevated inflation levels, likely stemming from government spending and loose monetary policies.

Similar to hyperinflation episodes after WW1, modern hyperinflation episodes were driven by expansionary fiscal policies, facilitated by a compliant central bank. The consequences of modern hyperinflation are far-reaching, including destroying accumulated financial savings, diminishing the central bank's credibility, and eliminating the role of money which forces the economy towards barter. The end of all modern episodes of hyperinflation required a consolidation in fiscal policy. However, both monetary and exchange rate policy were used, such as the implementation of fixed exchange rates. Inflation stabilization steps typically resulted in increases in unemployment and the real interest rate. In contrast to earlier bouts of hyperinflation, the end of modern hyperinflation does not result in an increase in demand for the domestic money. The diminished credibility of central banks leaves a legacy of dollarization and financial indexation. An example is how high-value purchases — like houses — are mostly completed in US dollars in Zimbabwe and Argentina.

What's evident is that institutions, such as a well-developed financial system and an independent central bank, play pivotal roles in mitigating the likelihood of high inflation episodes. Modern hyperinflation tends to be anticipated, often preceded by prolonged periods of high inflation. Ultimately, a consolidation in fiscal policy is essential to ending hyperinflation episodes. Hence, there may be some validity in the fiscal theory of the price level. In the long run, this influence may not be direct. While Friedman's assertion that sustained inflation is primarily driven by monetary policy holds true, the primary driver of an excessively expansionary monetary policy is often a combination of expansionary government spending and the absence of independent monetary institutions. Therefore, the predominant role of fiscal policy, in line with the fiscal theory of the price level, is likely the main driver of high inflation in the long run.

Conclusion

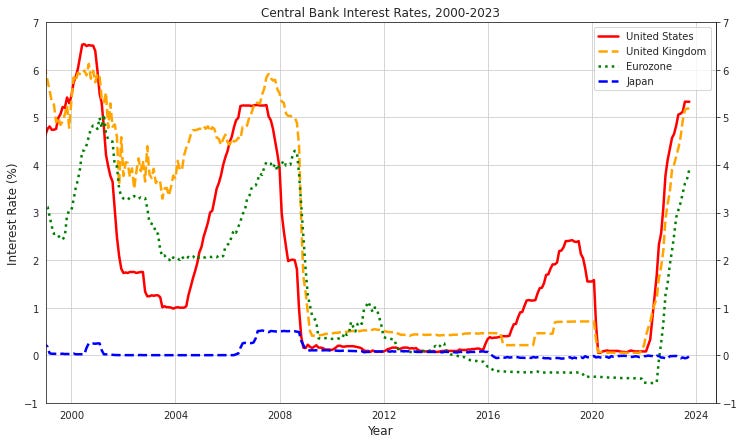

In conclusion, my own view of the recent surge in inflation it is likely temporary. The global shift toward more contractionary monetary policy, marked by the recent increase in interest rates, indicates a lack of sources to sustain inflation over an extended period. The recent supply shocks are expected to resolve themselves, and most of the world will probably revert to a state of relatively low inflation, as seen in the past few decades. While the prospect of very high public debt and fiscal deficits might suggest potential future inflation as governments consider printing money to repay debts, the complex experience of Japan complicates this assumption. The deeper question of when printing money drives inflation is an important one that I plan to answer in the next post.