"Mastery" by Robert Greene explores the process of achieving mastery in any field. The value of this book is that it presents a roadmap for achieving mastery by outlining several key ideas and strategies. Since this blog post is intended as a summary, it may miss many details, including several examples of individuals throughout history. In general, “Mastery” is better than the standard self-help book, there is some genuine wisdom.

The overall point of the book is that mastery is not simply a result of innate talent; but is attainable through a long process of intense focus, influenced by many factors that either help or hinder the journey. I hope to share some of those ideas. The world needs more people who are excellent at what they do, not only for the world to function better today, but also for a better tomorrow. Masters aren’t born, they are made. And there more of them, the better the world will be.

The Life’s Task

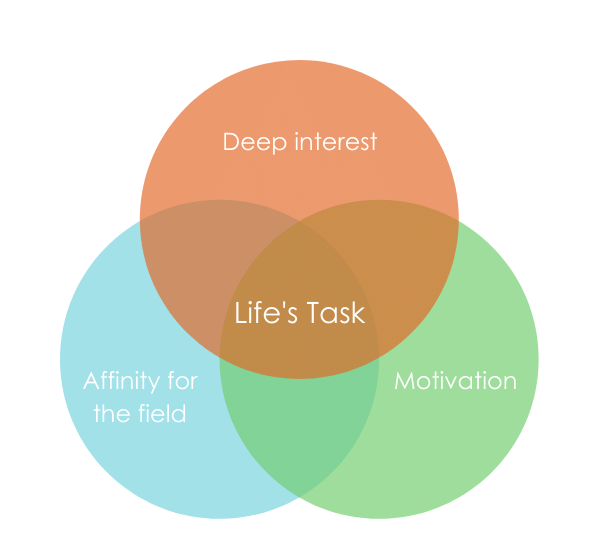

Getting good at anything is obviously not easy, it takes a vast amount of work and effort. So, the first step on the journey to mastery is in finding one's life's task — a vocation or pursuit that resonates deeply with an individual's inner passions. There is something for all of us to focus on and achieve mastery, a task to devote your life to. Greene states that one would “recognize it when you find it because it will spark that childlike sense of wonder and excitement; it will feel right”. Not choosing it could lead to the “false path”, which is one that does not align with your “deepest inclinations” and ultimately lead to regret.

The false path is often driven by external factors, such as the desire to impress others with “money, fame, or attention. Instead, our focus should be on pursuits that are “internally driven” — one that genuinely inspire and fulfil us.

Thus, passion is a central force in Greene's exploration of mastery. He suggests that genuine passion for a subject provides the drive and endurance required to overcome the likely obstacles and setbacks. Phil Knight, the founder of Nike, has a similar view:

“I’d tell men and women in their mid-twenties not to settle for a job or a profession or even a career. Seek a calling. Even if you don’t know what that means, seek it. If you’re following your calling, the fatigue will be easier to bear, the disappointments will be fuel, the highs will be like nothing you’ve ever felt.” (Shoe Dog, p.382)

The Apprenticeship Phase — The value of time

The next step in achieving mastery after choosing a “life’s task” is to aim for some sort of formal education -- if this is possible. After this is a second more practical education called the apprenticeship. The key to this is education involves practice, in which continued repetition and time spent on a skill result in it becoming natural and almost requiring no effort. Cal Newport in “So Good That They Can’t Ignore You” argues that one should put in effort into whatever opportunities you get, and then the passion will come after skills are obtained. Greene stresses the importance of adopting a long-term perspective on the path to mastery. Whatever path is chosen, it will take a while to achieve mastery:

“When it comes to mastering a skill, time is the magic ingredient” (p.77)

Malcom Gladwell spoke about the 10 000-hour rule required to achieve exceptional skill. This amounts to 6 to 10 years and is roughly the time required in the apprenticeship phase. At first, trying to be good at anything will seem difficult. But with consistent practice and repetition over a long period of time, some ability will be achieved. Establishing discipline, adopting a ritual and routine, and having a dedicated space for focus and concentration are all helpful in this journey. It is best to start small, become good at simple skills and build from there. Greene points out that natural gifts can also be a curse:

“Do not envy those who seem to be naturally gifted; it is often a curse, as such types rarely learn the value of diligence and focus, and they pay for this later in life” (p.45).

However, merely dedicating 10 000 hours of practice and repetition is not enough to achieve mastery — the eventual ease and comfort of repetition can result in complacency. Becoming exceptional at anything also requires a creative period involving trial and error — Greene compares it to the hacker approach to programming. This phase requires a commitment to continued learning, a willingness to try and create new things. It involves raking risks and working on areas where we may be weak, even if they result in more mistakes and failures. This effort could result in criticisms of peers or even the public, but this will help to reveal gaps in knowledge:

“Mistakes and failures are precisely your means of education. They tell you about your own inadequacies.” (p83)

Overall, the apprenticeship phase is a long period of practice that cannot be avoided. Whatever path is chosen, it will be long and difficult road. There is no room for instant gratification. This process will require perseverance and resilience to overcome the setbacks. There will likely be long periods without clear evidence of improvement, but you just must trust the process. Over time, the effort will be worthwhile. There really are no shortcuts. However, one useful way to shorten the period and the next step to mastery is to find a good mentor.

Find a Mentor

While the path to mastery is long and difficult, mentors can play a role in this process, guiding us when we are lost and have gone the wrong way, and helping us know which path to take.

“The reason you require a mentor is simple: Life is short; you only have so much time and so much energy to expend. Mentors do not give you a shortcut, but they streamline the process” (p.103)

Getting the right mentor is not easy. Greene suggests to first work on yourself, accumulating knowledge and obtaining a solid work ethic. Eventually to the point where you would be useful to a master. After putting in all the effort, some master will eventually find you interesting and become your mentor. One should also not be afraid to approach masters, while also building a social network overall:

“In any event, you should not feel timid in approaching Masters, no matter how elevated their position” (p.106)

Greene suggests that the ideal mentor is one that will provide “tough love”, such as realistic feedback. As mentioned before, this criticism can be useful, but receiving it from someone who has achieved mastery is worth a lot more. It is likely to be more honest and relevant than from other people.

If one cannot find the perfect mentor, it might be better to have several mentors with different strengths and weaknesses, each one filling the gaps in your knowledge and experience. This can also compound the effect of relationships.

However, it is sometimes not possible — due to location, lack of skills, contacts, or some other circumstances — to find even a single mentor. In such a case, Greene suggests that books can play a role as temporary mentors. In this situation, one has to deeply analyse both the book and the writer, in order to make them come alive and turn them into living mentors. These days, this could also be podcasts, blogs, YouTube videos, or online courses. There are now multiple mediums to learn from others whom you have not met, more so than ever before.

However, one cannot forever rely on a mentor for learning and support. The risk is that you become a poor copy of the mentor:

“As apprentices, we all share in this dilemma. To learn from mentors, we must be open and completely receptive to their ideas. We must fall under their spell. But if we take this too far, we become so marked by their influence that we have no internal space to incubate and develop our own voice, and we spend our lives tied to ideas that are not our own.” (p.119)

The solution to this is to take the mentor on only for a time. But eventually, after learning everything possible, one needs to create some distance and go on one’s own way. And hopefully, to the point of competing with the former mentor:

“As Leonardo da Vinci said, “Poor is the apprentice who does not surpass his master.”” (p.119)

The Role of Social Intelligence

Relying on a single relationship with a mentor is not enough to achieve mastery. Human beings are social beings, more so than any other animal. Thus, to achieve mastery, individuals inevitably need to be a part of a larger group, organization, and network. Given this, our ability to navigate the world depends on our social intelligence, which is our ability to interact and deal with people effectively. This is how Greene defines it:

“Social intelligence is the ability to see people in the most realistic light possible.” (p.125)

“Social intelligence involves focusing our attention outward instead of inward, honing the observational and empathic skills that we naturally possess” (p.136)

This is not easy; people are very complicated. But the effort is worth it. By learning to easily go through the social environment, one can devote more time to obtaining skills. Additionally, it helps to avoid being exploited and charm difficult people.

Greene provides a few tips to improve social intelligence, including regularly emphasizing the need to take peoples words with a grain of salt. Promises and words often have very little substance. Rather focus on actions, which tend to be more consistent and more likely to align with actual intentions. Also, promises aren’t often kept, so it’s better to rely on yourself to get things done.

“People will say all kinds of things about their motives and intentions: they are used dressing things up with word. Their actions, however, say much more about their character, about what is going on underneath the surface.” (p.139)

“It is best to cultivate both distance and a degree of detachment from other people’s shifting emotions so that you are not caught up in the process. Focus on their actions, which are generally more consistent, and not on their words.” (p.145)

In turn, Greene recommends to using your own words sparingly so that they have value. Instead, strive to communicate through the quality of your work:

“By remaining focused and speaking socially through your work, you will both continue to raise your skill level and stand out among all the others who make a lot of noise but produce nothing.” (pg152)

Another point that Greene makes is to avoid judgements based on initial impressions of people. Human beings were originally hunters, relying on tracking and endurance to catch prey. The result of honing this skill over thousands of years is that humans are generally good at using heuristics — decision making based off very limited information. However, relying on this heuristic to judge individuals can result in many errors, as people are far more complicated.

An important part of social intelligence mentioned by Greene is empathy. This is the ability to view things from the perspective of others and is essential for the ability to coordinate with others. It also helps to “see yourself from the outside” to see how your reputation is judged and formulated. A part of empathy is to avoid making others feel stupid, as “intelligence is the most sensitive trigger point for envy”.

When asking for a favour or help from someone, it should be angled to appeal to the individual’s self-interest. But also, be wary of others wanting to collaborate, as they might be thinking of their own self-interest and could be trying to find someone who will do the heavier lifting for them. Sam Altman, however, recommends helping others as much as possible, as a way to build a network and could result in others helping you. Adam Grant has a similar sentiment in the book “Give and Take”. An example is teaching others, which can be way of deepening understanding and filling in gaps.

The overall point is that being part of a larger social group is inevitable. People are complex, including those that are exploitive, manipulative and those that are supportive. People can either help you obtain more skills and share your work or do the opposite. Obtaining even the rudiments of social intelligence will help gain supporters and to be able to read and recognize the “sharks”. Thus, a greater understanding of other people will make obtaining mastery easier.

Be Creative

The knowledge obtained in the apprenticeship phase and from mentors provides the foundation for mastery. However, this is not enough; continuing with what has been done in the past can become boring:

“The problem for us all is that the knowledge we gain in the Apprenticeship Phase – including numerous rules and procedures – can slowly become a prison. It locks us into certain methods and forms of thinking that are one-dimensional.” (p.178)

Thus, as mentioned before, mastery also requires a creative phase. One in which you take risks and try new things using the knowledge and experience obtained. This will result in work that is genuinely innovative. Craig Wright in the “The Hidden Habits of Genius” recommends that the secret to creativity is to continue to have the childlike wonder of the world. Every child is blessed with a vivid imagination, but this declines as we age. Greene suggests that thinking in terms of images can be a way to return to this imaginative ‘childlike’ way and improve creativity. The idea is that thinking in terms of images allows us to bypass words and imagine many things at once:

“The use of images to make sense of the world is perhaps our most primitive form of intelligence, and can help us conjure up ideas that we can later verbalize.” (p.197)

Greene further suggests that working with our hands can help with this creative process. The “hand-brain connection is something deeply wired within us” and it can help to think in visual terms:

“When we work with our hands and build something, we learn to sequence our actions and how to organize our thoughts. In taking anything apart in order to fix it, we learn problem solving skills that have wider applications. Even if it is only as a side activity, you should find a way to work with your hands.” (p.64)

Yvon Chouinard, the founder and owner of Patagonia, has a similar view of the importance of working with one’s hands:

“When my son, Fletcher, was a teenager, I told him it didn’t matter to me what he wanted to do for work in the future as long as he also learned some sort of craft that involved working with his hands.” (Let My People Go Surfing, p.78)

“A study done of the most successful CEOs in America found one factor they all have in common They enjoy working with their hands.” (Let My People Go Surfing, p.171)

Creativity often requires hard work and an increase in intensity. Greene suggests that having some sort of tension can drive intensity and creativity, like “an army that is backed against the sea”. One way of creating tension is setting an arbitrary deadline to enhance concentration and eliminate other things that aren’t important:

“If you don’t have deadlines, manufacture them for yourself. The inventor Thomas Edison understood how much better he worked under pressure.” (pg201)

Overall creativity is the result of working very hard for a long time. It requires persistence and long periods of focus. There must be something inside of you to push on and keep going. There are no substitutes. There is limited room for impatience:

“When you look at the exceptionally creative work of Masters, you must not ignore the years of practice, the endless routines, the hours of doubt, and the tenacious overcoming of obstacles these people endured. Creative energy is the fruit of such efforts and nothing else.” (pg246)

While working hard is important for creativity, that doesn’t mean that we should strive to push as many hours with our heads down. Sometimes periods of relaxation can bring out some of the best ideas out of the stored long-term memory. Often creative insights arise from relaxed moments, such daydreaming or even showering. Craig Wright in the “The Hidden Habits of Genius” talks about the value of physical exercise for creativity. This shouldn’t be too tedious as this would require concentration. Instead, one should strive for something more leisurely like walking:

“It is only ideas gained from walking that have any worth- Nietzsche.” (Deepwork by Cal Newport, p.121)

Conclusion — Fuse it all together.

The final step of mastery according to Robert Greene is to expand one’s own knowledge away from ones chosen “life’s task” towards other fields. The idea is to replicate the stereotypical renaissance man or polymath – one who is excellent in multiple fields. This is always possible, alternatively one might to try to obtain more broad experiences. To be more like Isaiah Berlin’s fox than a hedgehog. The idea is that drawing from a wide range of experiences would lead to more creativity and innovation. According to Charles Duhigg in the book “Smarter, Faster, Better”, creativity is simply combining broad experiences:

““Creativity is just connecting things,” Apple cofounder Steve Jobs said in 1996. “When you ask creative people how they did something, they feel guilty because they didn’t really do it, they just saw something… That’s because they were able to connect experiences they’ve had and synthesize new things.”” (Smarter, Faster, Better, p.223)

“The method Robbins suggested for jump-starting the creative process – taking proven, conventional ideas from other settings and combining them in new ways – is remarkably effective.” (Smarter, Faster, Better, p.212)

The risk of this broad approach is that you may become a dilettante — merely average at many things. However, it is possible to get around this by working very hard. This is a repeated theme throughout the book, you can’t be a lazy master. It will require consistent effort over a long period of time, including periods of very high intensity and focus. It will also require help from others and embracing creativity.

Thus, the overall point of the book is that achieving mastery is difficult, no matter what path is taken. However, it is possible for anyone. We all have something to masters in, something to create and share with the world. The world would be a richer and more diverse place if we all strived to achieve it.